Anticoagulation Safety Calculator

Select Your Patient's Condition

Based on article: Kidney & Liver Disease Anticoagulation Guidelines

Why Anticoagulation Gets So Complicated in Kidney and Liver Disease

When someone has both kidney disease and liver disease, giving a blood thinner isn’t just about picking a pill. It’s like trying to balance a stack of fragile glasses while walking on ice. One wrong move, and things break-fast. The goal is to stop clots without causing a bleed, but both organs play critical roles in how these drugs work. When they’re damaged, the rules change. And the data? It’s messy. Most clinical trials for newer blood thinners (DOACs) excluded people with severe kidney or liver problems. So doctors are left guessing-based on limited evidence, scattered guidelines, and real-world experience.

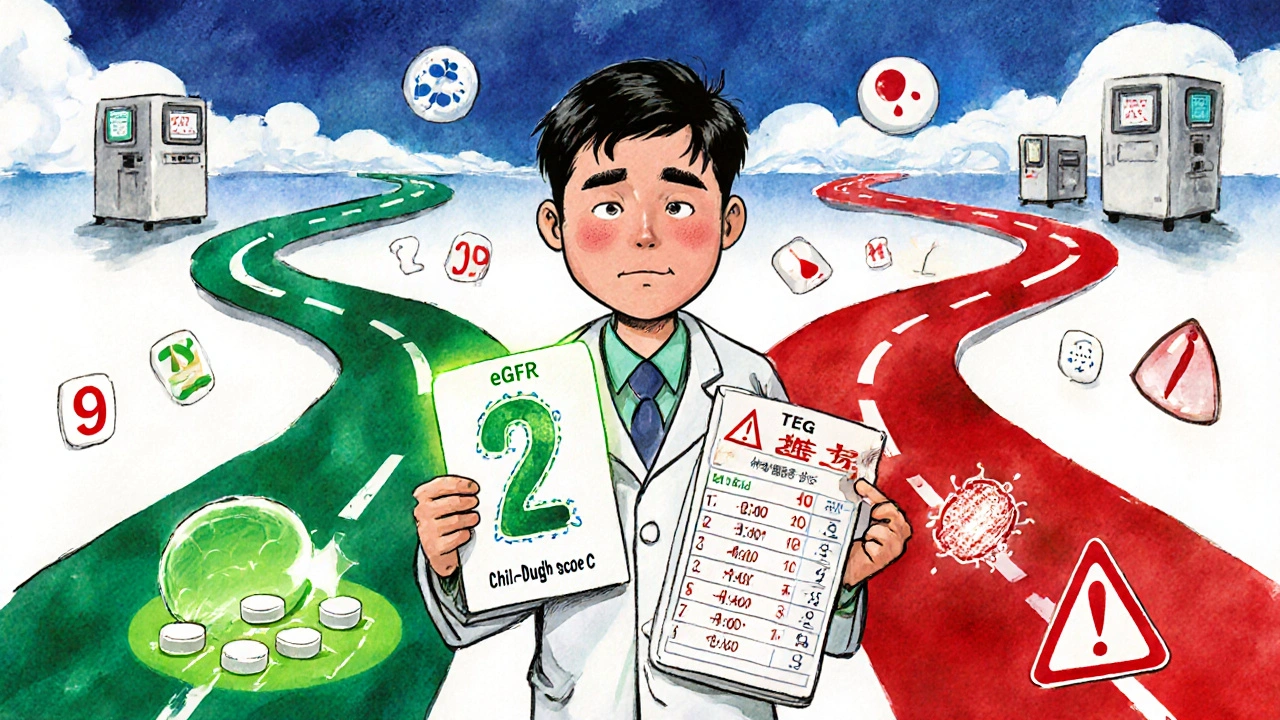

How Kidney Disease Changes the Game

Your kidneys filter drugs out of your blood. When they fail, those drugs build up. That’s why dose adjustments aren’t optional-they’re life-saving. For chronic kidney disease (CKD), the key number is eGFR, which measures how well your kidneys are working. Below 30 mL/min, you’re in stage 4 or 5. That’s where things get risky.

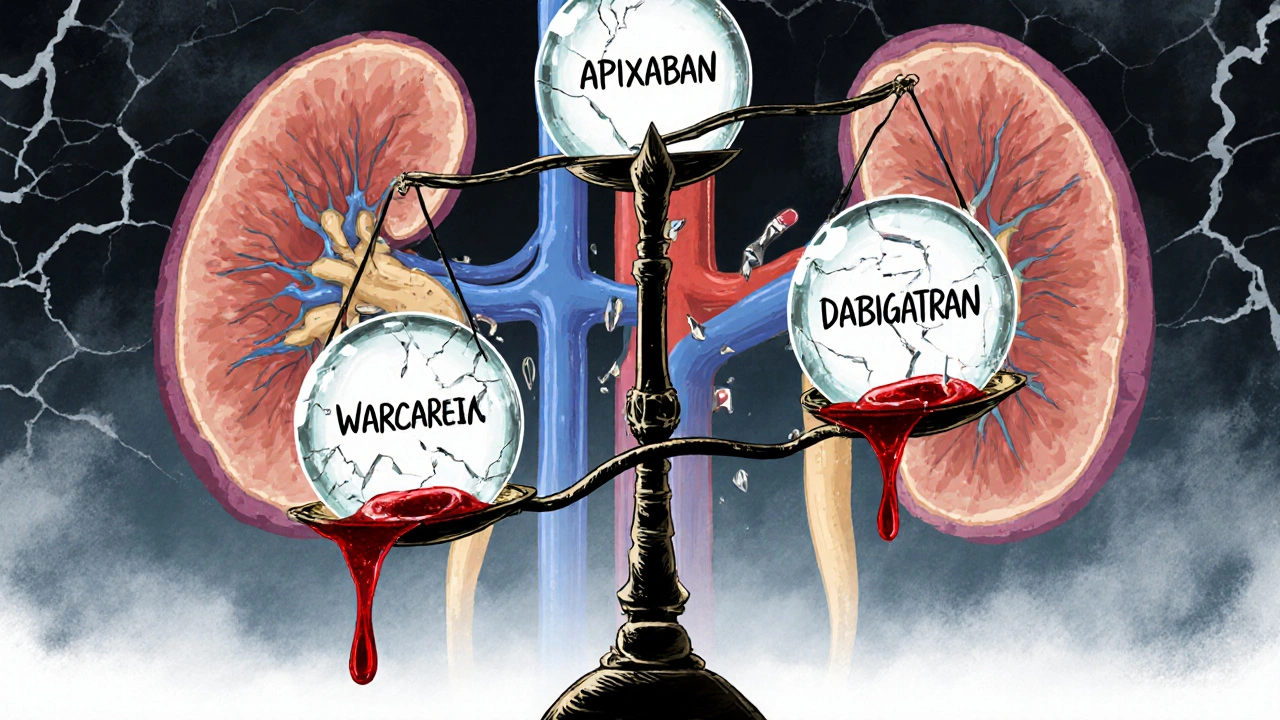

Apixaban is the most forgiving DOAC here. Even in dialysis patients, studies show it can be used at 2.5 mg twice daily. Why? Because only about 27% of it is cleared by the kidneys. Rivaroxaban and edoxaban? They’re mostly filtered out by the kidneys-so they’re not safe at this stage. Dabigatran? Out. About 80% of it leaves through the kidneys. Even a small dose can pile up and cause bleeding.

Warfarin doesn’t rely on kidney function, but it’s trickier to control. Your INR (a blood test that measures clotting time) becomes unstable in advanced CKD. Some experts recommend lowering the target INR to 1.8-2.5 instead of the usual 2.0-3.0. Why? Because the risk of bleeding goes up, and the benefit of preventing strokes doesn’t always keep pace.

Real-world data from 12,850 dialysis patients shows that only about 28% even got anticoagulation-even though most had high stroke risk. Of those who did, DOACs had fewer bleeds than warfarin. But strokes were about the same. That’s the trade-off: fewer bleeds, same stroke risk. For many, that’s worth it.

Liver Disease Makes Everything Unpredictable

The liver doesn’t just filter drugs-it makes the proteins that help your blood clot. In cirrhosis, that production drops. You get fewer clotting factors, but also fewer natural anticoagulants. So the body’s balance is thrown off. A low platelet count (common in liver disease) adds another layer of risk.

Doctors use the Child-Pugh score to grade liver damage: A (mild), B (moderate), C (severe). DOACs? Maybe okay in Child-Pugh A. Use caution in B. Avoid completely in C. Why? A 2017 study found people with Child-Pugh C had over five times the risk of major bleeding on DOACs compared to those with healthy livers.

Warfarin seems like the safer bet-until you look closer. INR doesn’t tell the full story in liver disease. It only measures a few clotting factors. It ignores low platelets, low fibrinogen, and other imbalances. So you might see an INR of 2.5 and think you’re in range-but the patient is still at high bleeding risk. That’s why some centers use TEG or ROTEM tests, which give a full picture of clotting. But only 38% of U.S. hospitals have them.

One big problem: portal vein thrombosis. This is a clot in the liver’s main vein. It’s common in cirrhosis. And treating it? That’s different than preventing stroke in atrial fibrillation. Some doctors will anticoagulate even in Child-Pugh B or C if the clot is active. The risk of dying from a clot can outweigh the risk of bleeding.

DOACs vs. Warfarin: The Real Differences

Let’s compare the two main options head-to-head.

- Apixaban: Best safety profile in CKD. Lowest bleeding risk among DOACs. Even works at low doses in dialysis. No specific reversal agent, but bleeding is less common.

- Rivaroxaban: Higher bleeding risk in advanced CKD. Not recommended in eGFR <30. Avoid in liver disease unless Child-Pugh A.

- Dabigatran: Too dependent on kidneys. Avoid if eGFR <30. Only reversal agent is idarucizumab-but it’s expensive and only works for this one drug.

- Warfarin: Works in both kidney and liver failure, but hard to control. Requires frequent INR checks. Reversible with vitamin K and fresh plasma. But patients spend less time in the target range-only 45% of cirrhotic patients stay in range, versus 65% in healthy people.

Here’s what the numbers say: DOACs cut intracranial bleeding by 62% compared to warfarin in CKD patients. That’s huge. Brain bleeds are often deadly. But in end-stage kidney disease, warfarin might still be better-especially if the patient has a mechanical heart valve. DOACs aren’t approved for that, and data is too thin to trust.

What Doctors Actually Do in Real Life

Guidelines give you a framework. Real life? It’s messy. A nephrologist in a Reddit thread described giving apixaban 2.5 mg daily to 15 dialysis patients over two years-with zero bleeds. Another reported a catastrophic retroperitoneal bleed in a similar patient. No two cases are the same.

Many hepatologists now check platelet function, not just platelet count. If platelets are below 50,000/μL or the MELD score is over 20, they often stop anticoagulation. Why? Because the bleeding risk skyrockets. But if the patient has a recent portal vein clot? They might keep going.

And then there’s the cost and access issue. Reversing DOACs isn’t easy. Andexanet alfa (Andexxa®) costs $19,000 per dose and isn’t available in most hospitals. Idarucizumab (Praxbind®) is cheaper but only works for dabigatran. Most hospitals don’t have a clear protocol for managing anticoagulation in patients with both kidney and liver disease. That’s why medication errors are 3.2 times more common in this group.

What’s Coming Next

Hope is on the horizon. Two major studies are underway. The MYD88 trial is comparing apixaban to warfarin in 500 dialysis patients with atrial fibrillation-results expected in 2025. The LIVER-DOAC registry is tracking over 1,200 cirrhotic patients on DOACs worldwide.

The FDA is considering updating apixaban’s label for end-stage kidney disease based on new modeling data. KDIGO, the global kidney disease group, is updating its guidelines in late 2024, incorporating 17 new real-world studies.

For now, the message is clear: anticoagulation in kidney and liver disease isn’t one-size-fits-all. It’s not about following a checklist. It’s about understanding the person-their liver function, their kidney numbers, their bleeding history, their clotting risk, and what matters most to them.

When to Stop

There are hard stops. If someone’s platelets drop below 50,000/μL and they have advanced liver disease, most experts stop anticoagulation. If their MELD score is above 20, the risk of bleeding outweighs the benefit. If they’re on dialysis and have a history of GI bleeding? Many doctors avoid DOACs entirely.

But if they’re stable, have no prior bleeds, and have a high stroke risk? Apixaban at 2.5 mg twice daily is often the best choice. It’s the only DOAC with enough data to support it in this group.

Bottom Line

You can’t treat kidney and liver disease the same way you treat a healthy person. The drugs behave differently. The risks shift. The tools we use to monitor them are flawed. But you can still make smart choices. Start with the lowest effective dose. Use apixaban if possible. Avoid dabigatran and rivaroxaban in advanced disease. Monitor closely. Talk to both a nephrologist and a hepatologist. And remember: sometimes, doing nothing is safer than doing something risky.

Can you use DOACs in patients on dialysis?

Yes-but only apixaban, at 2.5 mg twice daily. Other DOACs like rivaroxaban, edoxaban, and dabigatran are not recommended because they’re cleared mostly by the kidneys and can build up to dangerous levels. Warfarin is still used, but apixaban has shown lower bleeding rates in real-world studies. No DOAC is officially approved for dialysis patients, but apixaban is the only one with enough data to support cautious use.

Is warfarin better than DOACs for liver disease?

Not necessarily. Warfarin is easier to reverse and doesn’t rely on liver metabolism, but it’s hard to control in cirrhosis. INR readings are unreliable because the liver can’t make enough clotting factors. DOACs may be safer in Child-Pugh A or B patients, with fewer brain bleeds. But in Child-Pugh C, DOACs are contraindicated due to high bleeding risk. The choice depends on the stage of disease and the reason for anticoagulation.

Why is INR not reliable in liver disease?

INR only measures vitamin K-dependent clotting factors (II, VII, IX, X). In liver disease, the liver also makes fewer anticoagulant proteins, platelets drop, and fibrinogen levels fall. So even if the INR looks normal, the patient may still be at high risk of bleeding. Tests like TEG or ROTEM give a fuller picture of clotting ability, but they’re not widely available.

What’s the safest DOAC for someone with both kidney and liver disease?

Apixaban is the safest option when both organs are impaired. It has the lowest kidney clearance (27%), the most data in CKD, and the lowest bleeding risk among DOACs. But only if the liver disease is mild (Child-Pugh A) and kidney function isn’t below eGFR 15. If both are severely damaged, many experts avoid all DOACs and use warfarin with close monitoring.

Do I need to stop anticoagulation before a procedure?

Yes, but timing depends on the drug and the procedure. For apixaban, stop 24-48 hours before low-risk procedures. For major surgery or if kidney/liver function is poor, stop 72 hours ahead. Warfarin is stopped 5 days before surgery, and vitamin K or fresh plasma may be given to reverse it. Always consult a specialist-procedures in patients with dual organ disease carry much higher bleeding risk.

Evan Brady

November 19, 2025 AT 05:13Apixaban is the only DOAC I’ll even consider in stage 4 CKD. I’ve seen rivaroxaban turn a stable patient into a walking hematoma. One guy on 15mg daily with eGFR 22 bled out through his gums just brushing his teeth. Apixaban 2.5mg BID? He’s still alive, walking his dog, no clots. The data’s messy, but the clinical reality isn’t. Use what doesn’t kill you first.

Alex Boozan

November 19, 2025 AT 22:31Let’s be real-pharma pushed DOACs because they’re profitable, not because they’re safer. Warfarin’s been around for 70 years. We know its quirks. DOACs? We’re still playing whack-a-mole with bleeding events in cirrhotic patients. And don’t get me started on how labs don’t even track TEG in 62% of hospitals. It’s not medicine-it’s corporate risk transfer.

Jenny Lee

November 21, 2025 AT 18:26My aunt on dialysis got apixaban. No bleeds. No strokes. Just… alive. That’s the win.

Ram tech

November 23, 2025 AT 17:10why even try to anticoagulate these people? they gonna die anyway. why waste money on fancy pills when the liver's already a goner?

mithun mohanta

November 24, 2025 AT 06:53Let me just say-this entire field is a house of cards. DOACs? They’re not approved for severe CKD. Yet we prescribe them anyway. We’re not clinicians-we’re gamblers with INRs. And the worst part? We pretend we know what we’re doing. TEG? ROTEM? Only the elite hospitals have them. The rest of us are flying blind with outdated algorithms and wishful thinking. It’s not evidence-based medicine-it’s evidence-adjacent desperation.

Joshua Casella

November 24, 2025 AT 18:42I’ve been doing this for 18 years. I used to give warfarin to every CKD patient. Then I saw three intracranial bleeds in six months. After that, I switched to apixaban 2.5mg BID for anyone under eGFR 30. Bleeds dropped by 70%. Strokes? Still the same. So we traded one risk for a less catastrophic one. That’s not ideal-it’s pragmatic. And if you’re still pushing rivaroxaban in dialysis patients, you’re not being careful-you’re being reckless.

Saket Sharma

November 25, 2025 AT 06:18Child-Pugh C? Don’t even bother. DOACs = death sentence. Warfarin? Still dangerous, but at least you can monitor it. And if you’re thinking of anticoagulating for portal vein thrombosis in Child-Pugh C-you’re not a doctor, you’re a thrill-seeker. The liver’s already failing. Let it fail. Don’t add bleeding on top.

Brandon Lowi

November 25, 2025 AT 17:14They say ‘no reversal agent’ like it’s a flaw. But that’s the point. DOACs aren’t designed to be undone-they’re designed to be predictable. Warfarin? You need vitamin K, plasma, fresh frozen-three different systems, three delays, three chances to mess up. Apixaban? It just… goes away. In 12 hours. No chaos. No drama. No pharmacy calls at 3 a.m. Sometimes the best medicine is the one that doesn’t need a rescue plan.

Kevin Jones

November 26, 2025 AT 17:09INR is a lie in cirrhosis. It measures three factors. The liver makes twelve. You’re not assessing coagulation-you’re measuring a shadow. We’re diagnosing a ghost. And we wonder why patients bleed? It’s not the dose-it’s the illusion of control.

Richard Couron

November 27, 2025 AT 02:21Did you know the FDA approved DOACs based on trials that excluded 80% of the people who actually need them? That’s not science-that’s fraud. And now we’re poisoning dialysis patients with corporate-approved poison because the suits wanted a patent extension. Wake up. This isn’t medicine. It’s a financial instrument dressed in white coats.

Alexis Paredes Gallego

November 28, 2025 AT 00:50Apixaban in dialysis? That’s just a placebo with a price tag. The real reason it ‘works’ is because the patients are so sick they’re not moving. No movement = no clots. No clots = no stroke. Not because the drug worked-because they’re bedridden. And if you think that’s ethical, you’ve lost your soul.

Shravan Jain

November 29, 2025 AT 04:09the data is messy because the trials were designed by people who have never held a dialysis patient's hand. they measured outcomes like robots. real people bleed. real people die. and we still call this 'evidence-based'?

Erica Lundy

November 30, 2025 AT 14:45There is an ethical tension here that transcends pharmacology: we treat disease as if it were a technical problem to be solved, rather than a human condition to be borne. When we prescribe apixaban to a dialysis patient with a 60% one-year mortality, are we extending life-or merely postponing death with a pharmacological fiction? The absence of bleeding is not the same as the presence of well-being. We must ask not only ‘can we?’ but ‘should we?’-and whether our certainty is merely the arrogance of a profession that mistakes measurement for meaning.

Premanka Goswami

December 1, 2025 AT 19:52They’re hiding the truth. The real reason DOACs are used in CKD is because insurance won’t cover warfarin monitoring anymore. Labs stopped doing INRs. Pharmacies won’t stock vitamin K. It’s not about safety-it’s about billing codes. The patients? They’re just collateral in the healthcare profit machine.