Benzodiazepine-Opioid Risk Calculator

Calculate Combined Respiratory Risk

Based on CDC data showing ten-fold increased overdose risk when both drugs are used together. Input your current doses to see your risk level.

Combined Risk Level

Enter doses to see risk assessment

How this works: Based on CDC data showing benzodiazepines present in 16% of opioid deaths. The calculation uses established conversion factors to compare actual doses against documented risk thresholds.

Important: This tool provides general risk assessment only. Actual medical risk depends on individual factors including tolerance, health conditions, and other medications. Always consult with your healthcare provider.

When Benzodiazepine-opioid combination refers to the simultaneous use of benzodiazepines and opioids, either prescribed together or taken recreationally the risk of fatal breathing problems jumps dramatically. This isn’t just a simple sum of two depressant drugs; the two act on different breathing centers in the brain, creating a perfect storm that can shut down ventilation in minutes.

Key Takeaways

- The synergy between opioids and benzodiazepines triples the chance of fatal respiratory depression compared with either drug alone.

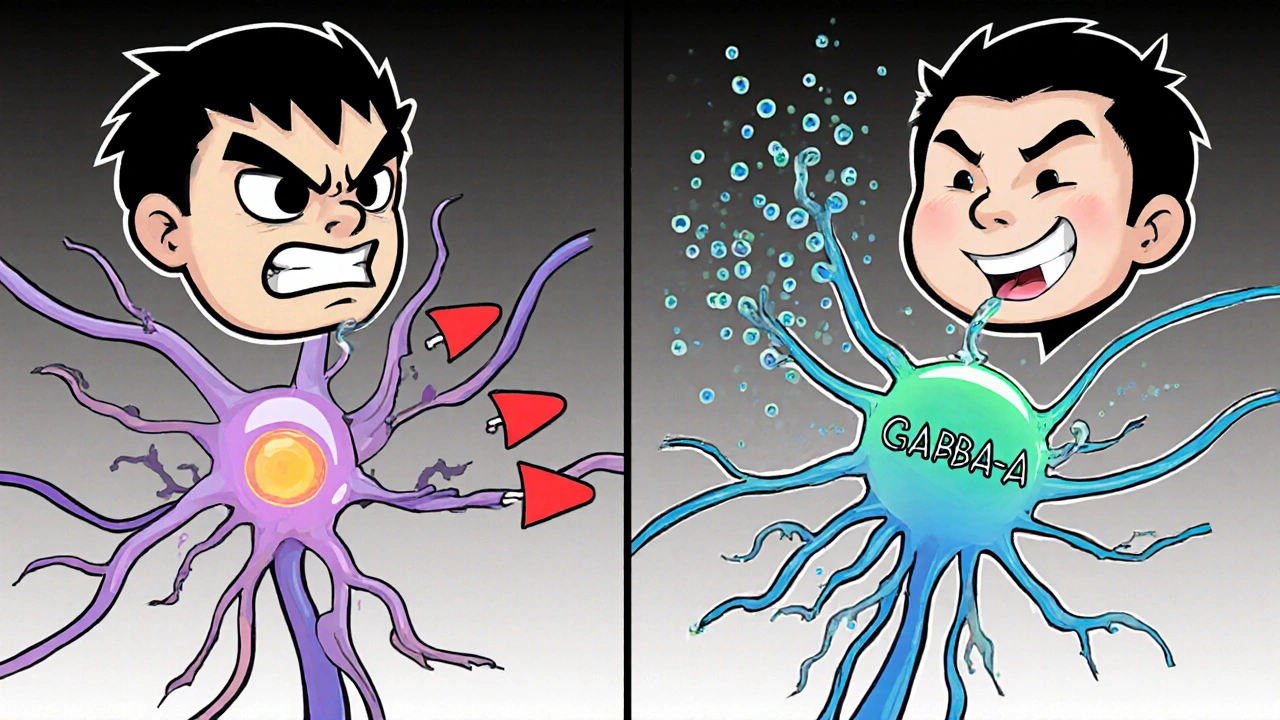

- Opioids blunt the brainstem’s inspiratory rhythm via mu‑opioid receptors, while benzodiazepines amplify GABA‑A inhibition across the same network.

- CDC data show that ~16 % of opioid overdose deaths in 2019 involved a benzodiazepine, and the risk of death is ten times higher when both are present.

- Clinical guidelines now urge clinicians to avoid concurrent prescribing, use the lowest effective doses, and monitor patients closely.

- Naloxone reverses opioid effects but does not address benzodiazepine‑induced depression; new research explores combined reversal agents.

How Opioids Cripple Breathing

Opioids bind to mu‑opioid receptors (MOR) in two key brainstem regions. In the preBötzinger Complex, MOR activation hyperpolarizes inspiratory neurons, slowing the rhythm that drives inhalation. In the Kölliker‑Fuse/Parabrachial (KF/PB) complex, opioids increase tonic expiratory drive, lengthening exhalation and often causing pauses between breaths.

Animal studies by Montandon et al. (2011, 2016) showed that removing MORs from KF neurons restores normal expiratory timing, while removing them from the preBötzinger Complex only helps at therapeutic opioid levels, not at overdose concentrations. The dual hit-slowed inhalation plus prolonged exhalation-produces a rapid drop in minute ventilation.

Benzodiazepines Add Their Own Suppressive Punch

Benzodiazepines boost GABA‑A receptor activity, increasing chlorine influx and silencing neurons throughout the central nervous system. At therapeutic doses, the impact on breathing is modest, but when GABA‑A activity spreads into the preBötzinger Complex and KF/PB, the already weakened respiratory drive is further throttled.

A 2018 study by Sun et al. demonstrated that fentanyl + midazolam cut minute ventilation by 78 %-far beyond the 45 % reduction with fentanyl alone. The combined effect is supra‑additive because opioids and benzodiazepines target different molecular pathways that converge on the same breathing circuitry.

Why the Combination Is Deadly

Statistical snapshots illustrate the scope:

- CDC reports benzodiazepines were present in 17 % of prescription‑opioid deaths and 22.5 % of illicit‑opioid deaths (2021).

- Patients prescribed both drug classes have a ten‑fold higher risk of fatal overdose (Dowell et al., JAMA Int Med 2016).

- Between 2004‑2011, emergency‑department visits for concurrent non‑medical use rose 131 % (FDA, 2016).

These numbers reflect a biologically driven synergy: opioids silence the inspiratory pacemaker while benzodiazepines amplify inhibition across the same network, leading to a profound, often irreversible, respiratory arrest.

Clinical Guidelines and Risk‑Mitigation Strategies

The 2016 CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain explicitly advises clinicians to avoid co‑prescribing benzodiazepines whenever possible. When the combination cannot be avoided, the guidelines recommend:

- Using the lowest effective doses of each drug.

- Limiting treatment duration (usually < 2 weeks for benzodiazepines).

- Implementing rigorous monitoring-pill counts, urine drug screens, and frequent follow‑ups.

- Leveraging prescription‑drug‑monitoring programs (PDMPs) to flag concurrent prescriptions.

- Educating patients and families about the signs of respiratory depression.

The FDA’s REMS for extended‑release opioids also requires prescribers to assess the necessity of a concurrent benzodiazepine and to document risk‑reduction steps.

Emergency Management: Reversal and Rescue

In an overdose scenario, naloxone remains the first‑line antidote for opioid‑induced depression. However, naloxone does nothing for the GABA‑mediated component. This limitation explains why some patients revive after naloxone but quickly relapse into shallow breathing.

Emerging research points to potential combined reversal agents. Ren et al. (2022) showed that the ampakine CX1739 restored normal breathing in rats after fentanyl + alprazolam exposure. While still experimental, such agents could become adjuncts to naloxone in the future.

Supportive measures-bag‑valve‑mask ventilation, end‑tidal CO₂ monitoring, and, in extreme cases, intubation-remain crucial while pharmacologic reversal takes effect.

Public Health Initiatives and Future Directions

National programs are tackling the problem from multiple angles:

- The CDC’s Enhanced State Opioid Overdose Surveillance program now tracks benzodiazepine involvement in real time.

- State PDMPs have added mandatory alerts for concurrent prescribing (16 states by 2020).

- The SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act (2018) requires Medicare Part D to run drug‑utilization reviews for high‑risk combinations.

- SA MHSA’s TIP 63 (2020) recommends non‑benzodiazepine anxiolytics-buspirone, SSRIs-when patients need opioid therapy.

Funding streams like the NIH’s HEAL Initiative have earmarked $15.7 million for research on combined central nervous system depressants. Promising avenues include:

- Developing bifunctional reversal agents that antagonize both MOR and GABA‑A receptors.

- Deploying AI‑driven PDMP algorithms that flag high‑risk prescribing patterns instantly.

- Inventing wearable “breathing pacemakers” that deliver rhythmic stimulation during an overdose event.

Even with these advances, CDC forecasts predict 12 000‑15 000 combined‑drug overdose deaths annually through 2025, underscoring the need for continued vigilance.

Quick Reference Table: Key Statistics and Recommendations

| Metric | Value | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Percentage of opioid deaths involving benzodiazepines (2019) | 16 % | Significant overlap; targeted monitoring needed |

| Risk multiplier for death when both drugs are used | ×10 | Elevated vigilance for any co‑prescribing |

| Emergency‑department visit increase (2004‑2011) | +131 % | Emerging public‑health crisis |

| Reduction in concurrent prescribing after FDA black‑box (2016‑2022) | ‑14.5 % | Policy works, but gaps remain |

| Annual combined overdose deaths (projected 2025) | 12 000‑15 000 | Continued need for safer therapies |

Frequently Asked Questions

Why does adding a benzodiazepine make an opioid overdose more lethal?

Opioids shut down the inspiratory rhythm by binding mu‑opioid receptors, while benzodiazepines boost GABA‑A inhibition throughout the same breathing circuits. The two mechanisms act on different parts of the respiratory network, producing a combined effect that is far greater than the sum of each drug alone.

Can naloxone reverse a benzodiazepine‑opioid overdose?

Naloxone reverses only the opioid component. The benzodiazepine‑related depression persists, which is why patients sometimes need additional respiratory support or experimental agents like CX1739.

What alternatives exist for anxiety treatment in patients on chronic opioids?

Non‑benzodiazepine options such as buspirone, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), or cognitive‑behavioral therapy are recommended. These avoid the synergistic respiratory risk while still managing anxiety.

How do prescription‑drug‑monitoring programs help?

PDMPs collect dispensing data in real time. Alerts can flag when a patient receives both an opioid and a benzodiazepine, prompting the prescriber to reassess therapy or seek alternatives.

Is there any promising research on a single antidote for both drugs?

Early animal studies on the ampakine CX1739 show it can reverse combined respiratory depression, but human trials are still pending. Researchers are also exploring bifunctional molecules that block both MOR and GABA‑A receptors.

Barbara Ventura

October 26, 2025 AT 19:20Wow, this article really lays out the danger, and the numbers are staggering, especially the 10‑fold increase, it's scary, yeah!!!

laura balfour

November 9, 2025 AT 16:40Honestly, reading through this feels like watching a thriller where the villain is a cocktail of chemistry, and the stakes are our very breaths. The synergy between opioids and benzos is not just additive; it's a perfect storm that ripples through the brainstem's rhythm generators. The preBötzinger Complex, that tiny pacemaker for inhalation, gets quieted by mu‑opioid receptors, while the KF/PB complex experiences a prolonged exhalation drive. Then benzodiazepines swoop in, cranking up GABA‑A inhibition across the same network, turning a dim light into a blackout. Think about the CDC statistic: 16 % of opioid deaths in 2019 had a benzo on board – that’s not a footnote, it’s a headline. And the risk multiplier of ten? That’s like saying a regular house fire suddenly becomes a nuclear explosion. The guidelines are trying to rope us in, telling doctors to keep doses low and monitor closely, but the reality on the streets is that many patients never get that level of oversight. Emergency departments saw a 131 % surge in visits for concurrent non‑medical use between 2004 and 2011 – numbers that read like a warning siren. And while naloxone can pull the opioid plug, it does nothing for the benzo‑driven GABA flood, leaving patients gasping for air again. Researchers are even looking at ampakines like CX1739 as a possible dual‑action rescue, but that’s still in the lab. The public‑health push with PDMP alerts and the SUPPORT Act tries to stitch the safety net, yet projections still point to 12‑15 k combined deaths annually through 2025. So what’s the takeaway? If you’re on either drug, ditch the other. If you can’t, at least stay hyper‑vigilant, keep meds in sight, and have naloxone on hand, because the clock is ticking the second you combine them.

Ramesh Kumar

November 23, 2025 AT 14:00Great summary! Just to add, the preBötzinger Complex is crucial for generating the inspiratory rhythm, and opioids really blunt that activity. Benzodiazepines, on the other hand, spread GABA‑mediated inhibition beyond the usual scope, which compounds the problem. Clinicians should definitely use the lowest effective doses and consider alternatives like buspirone for anxiety when opioids are needed.

ahmed ali

December 7, 2025 AT 11:20Look, I get the fear mongering vibe here, but let’s not pretend the solution is as simple as “just don’t mix them”. In real‑world practice, many chronic pain patients also suffer from severe anxiety, and the only thing that keeps them functional might be a low‑dose benzo alongside a steady opioid regimen. Sure, the studies show elevated risk, but they also often involve supratherapeutic doses, which isn’t the case for every prescription. Moreover, the PDMP alerts can generate alert fatigue; doctors start ignoring them because they pop up for every little thing. You can’t just swing a hammer and expect to nail every overdose problem down – you need nuanced guidelines, not blanket bans that push patients toward illicit markets. And don’t forget, the data on combined reversal agents like CX1739 are still in rodents; we’re a long way from a clinical magic bullet. So, while the caution is appreciated, let’s keep the conversation grounded in the complexities of patient care rather than dramatic headlines.

Deanna Williamson

December 21, 2025 AT 08:40This looks like another attempt to scare people without offering real solutions. The data is cherry‑picked and the tone is overly dramatic. We need balanced information, not panic.

Miracle Zona Ikhlas

January 4, 2026 AT 06:00Stay safe, friends!

naoki doe

January 18, 2026 AT 03:20Got a buddy who’s on both meds – they’re on strict follow‑up and keep a naloxone kit handy. It’s all about the monitoring.

Carolyn Cameron

February 1, 2026 AT 00:40It is incumbent upon us, as stewards of public health, to recognize the pernicious interplay between opioid and benzodiazepine pharmacodynamics. The extant literature, replete with quantitative analyses, unequivocally delineates a ten‑fold augmentation in mortality risk. Accordingly, prescribers must exercise judicious discretion, invoking the lowest efficacious dosages and instituting rigorous surveillance protocols. Moreover, the integration of advanced prescription‑drug‑monitoring systems could ameliorate inadvertent co‑prescribing. Ultimately, a concerted interdisciplinary effort is requisite to attenuate this grave epidemiological concern.

sarah basarya

February 14, 2026 AT 22:00This is just alarmist nonsense.