What You See Isn’t Always What’s There

Two people with the same blurry vision might have completely different problems. One could have early diabetic damage hiding under the surface. Another might be losing vision from tiny blood vessels leaking where no one can see them. That’s why eye doctors don’t just look into your eyes with a light anymore. They use OCT, fundus photos, and angiography - three powerful tools that show what’s really happening inside your retina, down to the level of single cells.

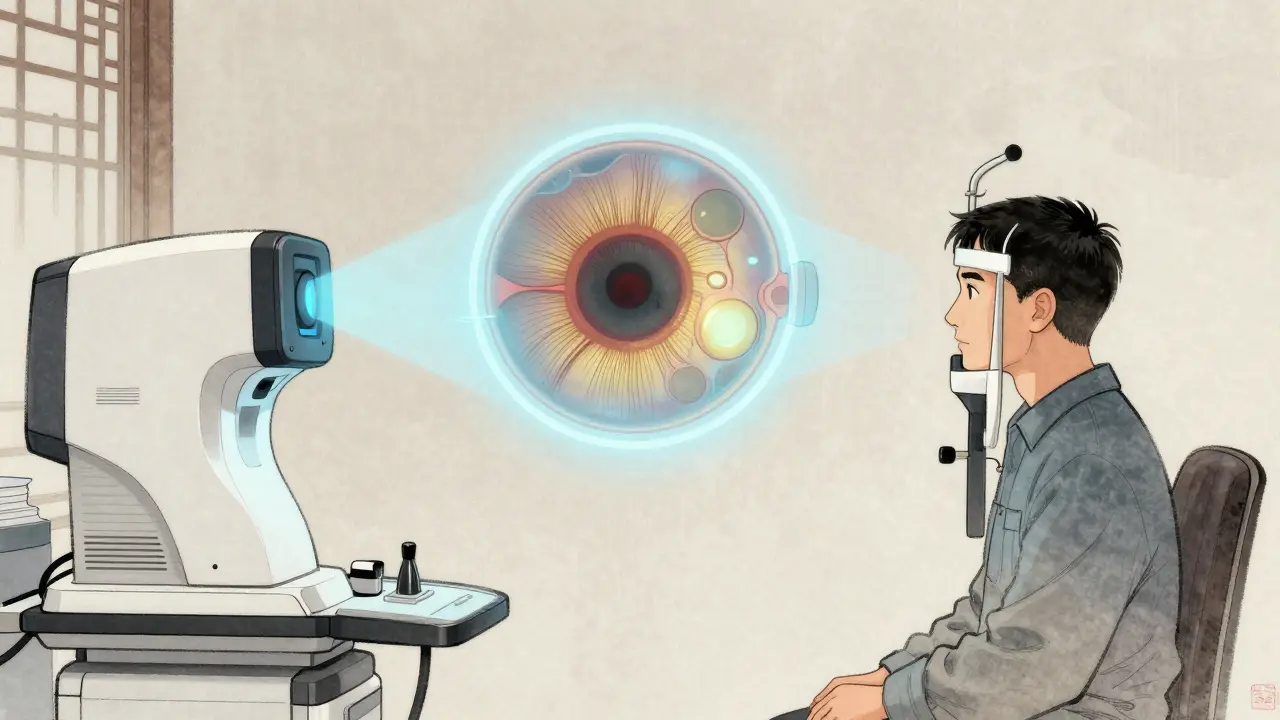

Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): The Retinal Microscope

OCT is like an ultrasound for your eye, but it uses light instead of sound. It doesn’t touch your eye. It doesn’t need drops or dyes. In under a minute, it builds a detailed cross-section of your retina - layer by layer. You can see the nerve fibers, the photoreceptors, the fluid pockets, even tiny scars from past damage.

Modern spectral-domain OCT (SD-OCT) gives images with 5-7 micrometers of resolution. That’s thinner than a human hair. Swept-source OCT (SS-OCT), the newer version, goes deeper and faster, scanning up to 400,000 times per second. It shows not just the retina but the choroid underneath - the layer that feeds it blood. This matters because diseases like age-related macular degeneration and punctate inner choroidopathy start there.

Doctors use OCT to spot macular holes, measure swelling from diabetic retinopathy, track glaucoma damage, and even see cholesterol crystals in Coats disease. In one study, OCT found exudates in 82% of Coats disease eyes that fundus photos missed. It’s the go-to tool when you need to know the anatomy - not just the surface.

Fundus Photography: The Retina’s Snapshot

Fundus photography captures a wide, color image of the back of your eye: the optic nerve, the macula, the blood vessels. Cameras like the Zeiss FF 450+ take these in seconds. It’s the baseline image - the photo you keep on file. It shows bleeding, swelling, drusen, and abnormal vessels clearly.

But it’s flat. It doesn’t show depth. A dark spot on a fundus photo could be a bleed, a scar, or a shadow from a cataract. That’s why it’s never used alone. It’s the map. You need OCT and angiography to read the terrain.

For diabetic retinopathy, fundus photos are still the standard for screening. They’re cheap, fast, and great for spotting early changes. But they can’t tell you if fluid is leaking inside the retina. That’s where OCT comes in. And if you’re trying to find where the blood vessels are growing abnormally? That’s where angiography steps in.

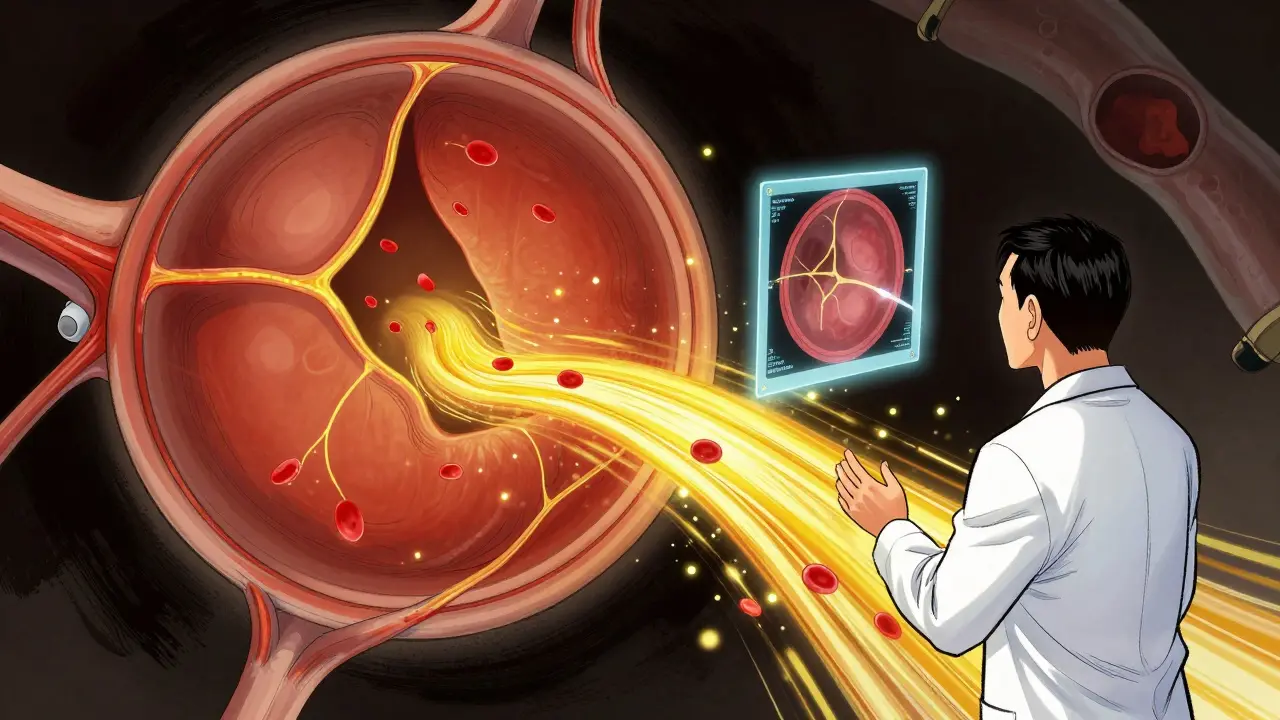

Fluorescein Angiography: The Dye That Reveals Blood Flow

Fluorescein angiography (FA) has been around since the 1960s. A yellow dye is injected into your arm. As it travels through the blood vessels in your eye, a special camera takes rapid-fire photos. The dye lights up the vessels - showing where they’re leaking, blocked, or growing where they shouldn’t.

It’s still the gold standard for spotting microaneurysms, capillary dropout, and neovascularization - the dangerous new blood vessels that cause vision loss in diabetic retinopathy and retinal vein occlusions. In one study, FA was 100% sensitive in detecting diabetic macular edema, while OCT only caught 79%.

But FA has downsides. It’s invasive. You might feel nauseous. You might turn yellow for hours. Rarely, you could have an allergic reaction. And it’s slow - 10 to 30 minutes per session. The images are also two-dimensional. You can’t see how deep the leak is. You can’t separate the layers of the retina like you can with OCT.

OCT Angiography (OCTA): The Dye-Free Revolution

Imagine seeing blood flow in your retina without a needle. That’s OCT angiography. It uses the same OCT machine but analyzes tiny movements of red blood cells to create 3D maps of the capillaries. No dye. No injection. Just a quick scan - often under 10 seconds.

OCTA shows the superficial, middle, and deep capillary plexuses separately. That’s huge. In diabetic retinopathy, it can detect early capillary loss before any visible damage appears on fundus photos. In Coats disease, it spots abnormal vessels that FA might miss. In punctate inner choroidopathy, OCTA revealed non-perfused areas in the choroid that no other test could see.

Studies show OCTA detects more neovascularization than FA in some cases. It’s especially good at finding small, peripheral changes - things you’d need a wide-field camera to catch. But it’s not perfect. It can’t show leakage. It’s fooled by motion. If you blink, or your eye drifts, the image gets blurry. And it doesn’t work well if your cornea is cloudy or your pupil is small.

Still, it’s becoming the new standard for monitoring. Patients love it. Doctors love it. It’s fast, safe, and repeatable. You can do it every few months without worry.

How Doctors Use Them Together

No single tool tells the whole story. That’s why every retinal specialist uses a combination.

- Diabetic retinopathy: Fundus photo for screening, OCT for swelling, OCTA for early vessel loss, FA only if treatment decisions depend on leakage.

- Age-related macular degeneration: OCT for fluid and drusen, OCTA for choroidal neovascularization, FA if OCTA is unclear or if there’s bleeding.

- Retinal vein occlusion: OCT for macular edema, FA for ischemia and neovascularization risk.

- Coats disease: Fundus photo for the big picture, OCT for hidden exudates and fluid, OCTA for abnormal vessels, FA if OCTA is inconclusive.

- Punctate inner choroidopathy: OCT for lesions, FA and ICG for inflammation, OCTA for choroidal perfusion.

One 2023 study found that 48 out of 84 retinal tumors were better seen with swept-source OCTA than spectral-domain OCTA. But the numbers weren’t identical. You can’t swap one for the other. Each has its own quirks. That’s why expertise matters. A trained eye knows when to trust OCT, when to push for FA, and when OCTA is the missing piece.

What’s Next?

AI is starting to analyze OCT and OCTA images automatically - flagging early signs of disease before a doctor even sees them. Wide-field OCTA now covers more than 80% of the retina, catching problems in the far periphery that used to require multiple FA sessions.

But the biggest change? Patients are getting better care because tests are faster, safer, and more precise. You no longer need to fear dye injections for routine monitoring. You don’t need to wait weeks to track progress. You can see your own retinal layers change over time - and know exactly when to act.

Why This Matters to You

If you have diabetes, high blood pressure, or a family history of macular degeneration, these tests aren’t optional. They’re your early warning system. A single OCT scan can catch swelling before you notice vision loss. OCTA can show you’re losing capillaries before you even feel it. And fundus photos? They’re the record that lets your doctor compare year to year.

Don’t wait until your vision blurs. If your doctor recommends imaging, ask: Which test are you ordering, and why? You deserve to know what’s happening inside your eyes - not just what’s visible on the surface.

Is OCT safe? Does it hurt?

OCT is completely painless and non-invasive. No drops, no dyes, no contact with your eye. You sit in front of the machine, look at a light, and hold still for a few seconds. It’s like having a photo taken - but of the inside of your eye. It’s safe for children, pregnant women, and people with allergies.

Is fluorescein angiography dangerous?

Fluorescein angiography is generally safe, but it involves an IV injection of dye. Common side effects include temporary yellow skin, nausea, or a metallic taste. Serious allergic reactions are rare (less than 1 in 10,000), but can include vomiting, hives, or breathing trouble. That’s why clinics always have emergency equipment on hand. If you’ve had a reaction before, tell your doctor - they may skip FA or use an alternative.

Can OCTA replace fluorescein angiography completely?

Not yet. OCTA is excellent for showing blood vessel structure and blockages - but it can’t show leakage. If your doctor needs to know if fluid is oozing from a vessel (common in diabetic macular edema or vein occlusions), FA is still needed. Think of OCTA as the map of the roads, and FA as the camera that shows which ones are leaking.

How often should I get these scans?

It depends on your condition. For stable macular degeneration, once a year may be enough. For active diabetic retinopathy or recent treatment, every 3-6 months is common. If you’re monitoring a new diagnosis, your doctor might start with monthly scans to track progress. There’s no one-size-fits-all - it’s based on your risk, your symptoms, and how your eyes respond to treatment.

Do I need to prepare for these tests?

For OCT and OCTA, no preparation is needed. For fundus photography, your pupils may be dilated - which can make your vision blurry for a few hours. For fluorescein angiography, you’ll need someone to drive you home because of the dilation and potential side effects. Wear sunglasses afterward. Avoid sunlight until the dye clears.

Solomon Ahonsi

February 2, 2026 AT 20:57George Firican

February 4, 2026 AT 10:17Matt W

February 6, 2026 AT 07:49Akhona Myeki

February 7, 2026 AT 02:47Sandeep Kumar

February 7, 2026 AT 16:44Vatsal Srivastava

February 8, 2026 AT 04:59Brittany Marioni

February 9, 2026 AT 10:56Nick Flake

February 11, 2026 AT 07:44