TNF Inhibitor TB Reactivation Risk Calculator

Patient Assessment

When you start a TNF inhibitor for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, or Crohn’s disease, you’re getting powerful relief from inflammation. But behind that relief is a quiet danger: TNF inhibitors can wake up dormant tuberculosis (TB) in your body. This isn’t theoretical. In real-world clinics, patients on these drugs are developing active TB-sometimes within months of their first dose. And not all TNF inhibitors carry the same risk.

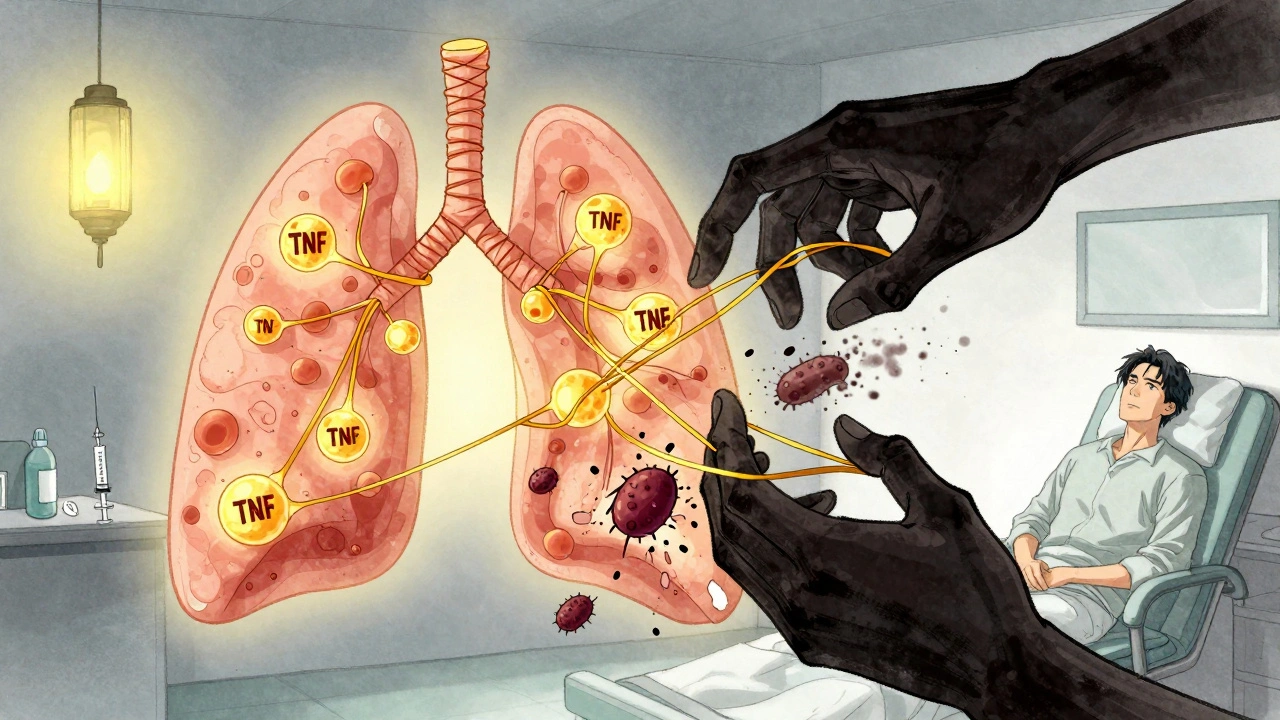

Why TNF Inhibitors Reactivate TB

Your body keeps TB bacteria in check by building tiny walls of immune cells around them, called granulomas. These walls hold the infection in place, keeping you symptom-free. That’s latent TB infection (LTBI)-you’re infected, but not sick. TNF-alpha is the glue that holds those granulomas together. When you block TNF-alpha with a drug, those walls start to crumble. Not all TNF blockers are the same. There are two main types: etanercept (a soluble receptor) and monoclonal antibodies like infliximab and adalimumab. The antibody types bind tightly to both free-floating and cell-bound TNF-alpha. That’s the problem. Cell-bound TNF-alpha is what keeps granulomas intact. Etanercept doesn’t bind as strongly to the cell-bound version, so it’s less likely to break down those walls. That’s why studies show patients on infliximab or adalimumab are more than three times as likely to develop TB as those on etanercept.Who’s at Risk?

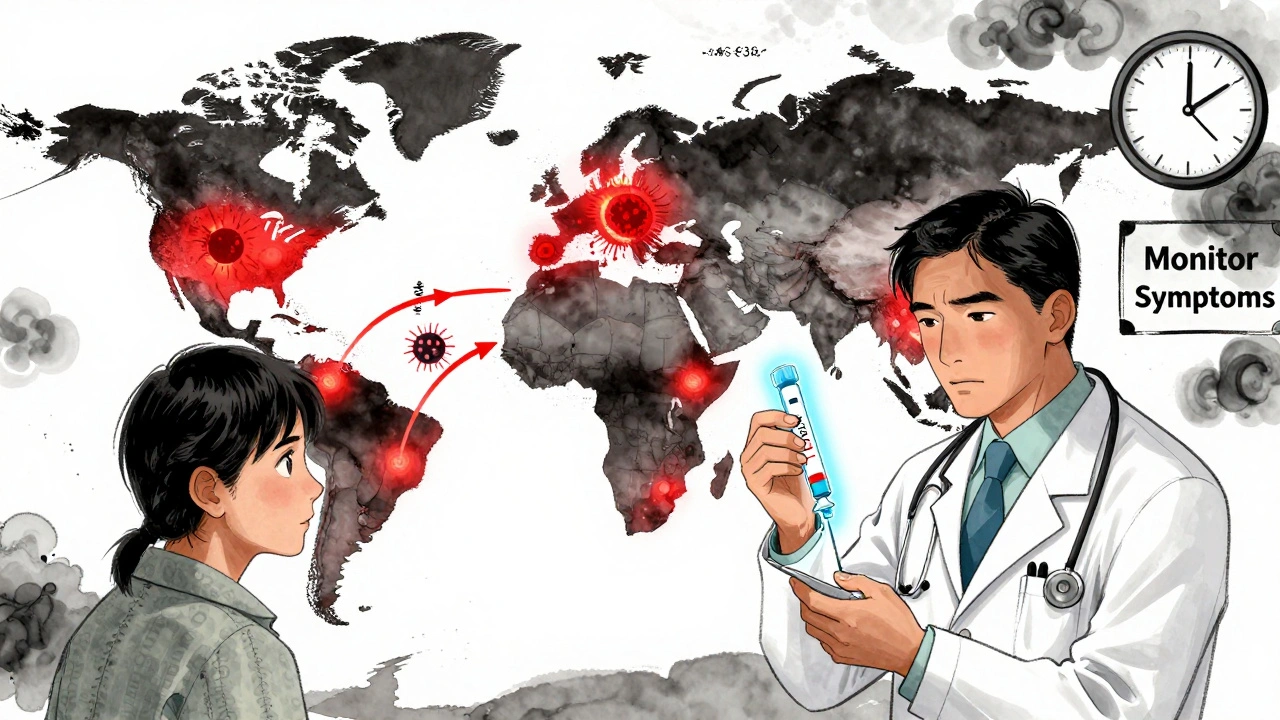

Anyone on a TNF inhibitor is at risk, but some faces higher danger. If you were born in or lived for a long time in a country with high TB rates-India, the Philippines, Nigeria, Vietnam, or parts of Eastern Europe-you’re at much greater risk. Even if you’ve lived in the UK or US for years, your past exposure matters. TB can lie dormant for decades. Age also plays a role. Older adults are more likely to have had past exposure. People with diabetes, kidney disease, or who’ve had organ transplants are also more vulnerable. And if you’ve had TB before-even if you were treated-you’re still at risk. The bacteria can hide in scar tissue, waiting for the right moment to return.Screening Before You Start

Before you get your first TNF inhibitor shot or infusion, you must be screened for latent TB. There are two main tests: the tuberculin skin test (TST) and the interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA). Both look for your immune system’s memory of TB bacteria. In practice, TST is still more common because it’s cheaper and easier to do. But IGRA is more accurate, especially if you’ve had the BCG vaccine (given in many countries to prevent TB). The BCG vaccine can cause false positives on TST. IGRA doesn’t get fooled by that. Guidelines say: do one or the other. Some clinics do both, especially for high-risk patients. A 2024 study from a major UK hospital found that 87% of patients got a TST, but only 6% got IGRA. That’s not enough. For people from high-TB-burden countries, IGRA should be the first choice.What If You Test Positive?

If your test comes back positive, you don’t start the TNF inhibitor right away. You treat the latent TB first. The old standard was nine months of isoniazid. That’s effective-but hard to stick with. Side effects like liver damage, nausea, and fatigue make many people quit. A 2023 FDA-approved option is a four-month course of rifampin and isoniazid. It’s just as effective, and patients are nearly 90% more likely to finish it. Some doctors now use a three-month course of rifampin alone, especially if liver concerns are high. The key is to complete the treatment. Studies show that even if you get screened and treated, you’re still at risk if you don’t finish the full course. One hospital study found that 32% of patients stopped their TB meds because they were scared of side effects. That’s dangerous.

Monitoring After You Start

Screening isn’t a one-time thing. TB can strike even if your test was negative. Why? Because you might have been recently infected and your immune system hasn’t reacted yet. Or the test missed it. About 18% of TB cases in TNF inhibitor patients had negative screening results before treatment. That’s why you need ongoing monitoring. Every three months for the first year, your doctor should ask: Have you had a fever? Night sweats? Unexplained weight loss? A cough that won’t go away? These are red flags. Don’t wait. If you feel any of these, get checked immediately. TB on TNF inhibitors often isn’t in the lungs. It’s in the spine, brain, liver, or lymph nodes-extrapulmonary TB. That makes it harder to diagnose. A chest X-ray might look normal. Blood tests might not show anything. You need a high index of suspicion.The Hidden Risk: TB-IRIS

There’s another twist. If you develop TB while on a TNF inhibitor and then start TB treatment, your immune system can overreact. This is called TB-IRIS-immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. Your body, suddenly freed from TNF suppression, goes into overdrive trying to kill the TB. But it ends up attacking your own tissues. You get fever, swelling, pain-all signs of inflammation, even though you’re treating the infection. TB-IRIS happens in about 13% of patients who start TB treatment while still on TNF inhibitors. It often appears 45 days after starting TB drugs and 110 days after the last TNF dose. Treatment usually requires steroids-sometimes for months. It’s not common, but it’s serious. And it’s preventable: if you delay starting TNF inhibitors until after you’ve completed TB treatment, you lower the risk.Different Drugs, Different Risks

Here’s what the data says about the three most common TNF inhibitors:| Drug | Class | TB Reactivation Risk | Key Reason |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infliximab (Remicade) | Monoclonal antibody | High | Binds strongly to membrane-bound TNF, disrupts granulomas |

| Adalimumab (Humira) | Monoclonal antibody | High | Same mechanism as infliximab; similar risk profile |

| Etanercept (Enbrel) | Soluble receptor | Low | Does not strongly bind membrane-bound TNF; preserves granuloma integrity |

What About Biosimilars?

Biosimilars of adalimumab and infliximab are now widely used. They’re cheaper-around $4,500 a month instead of $6,700. But do they carry the same TB risk? Yes. They’re designed to work exactly like the originals. The same screening and monitoring rules apply. Don’t assume a biosimilar is safer. It’s not.Global Disparities

In the UK, TB rates are low-about 7 cases per 100,000 people. But in places like India or South Africa, it’s over 200 per 100,000. In those countries, many rheumatology clinics don’t even have access to IGRA tests. That’s a huge gap. The World Health Organization says 80% of clinics in low-resource settings lack reliable TB screening tools. Even in the UK, patients from high-burden countries often face delays. Some doctors are afraid of giving TB treatment to people who might not return for follow-up. Others worry about liver toxicity. But skipping screening or treatment isn’t an option. The consequences-disseminated TB, meningitis, death-are too high.What’s Next?

Scientists are working on new drugs that block TNF without breaking granulomas. Early animal studies show a new class of selective TNF inhibitors reduces TB reactivation by 80% compared to current drugs. These are still in trials, but they offer real hope. Until then, the rules are clear: screen before you start. Treat latent TB. Monitor every three months. Don’t ignore symptoms. And choose your drug wisely.TNF inhibitors save lives. But they also carry a silent threat. The difference between safety and disaster often comes down to one question: Did you get tested?

Can you get TB even if your screening test is negative?

Yes. About 18% of TB cases in TNF inhibitor users occurred in people with negative screening results before treatment. This can happen if you were recently infected and your immune system hasn’t responded yet, or if the test missed the infection. That’s why ongoing monitoring for symptoms like fever, night sweats, and cough is just as important as initial screening.

Which TNF inhibitor has the lowest risk of TB reactivation?

Etanercept has the lowest risk. Unlike infliximab and adalimumab, it doesn’t strongly bind to membrane-bound TNF-alpha, which is essential for keeping TB bacteria contained in granulomas. Studies show patients on etanercept are 3 to 5 times less likely to develop TB than those on antibody-type inhibitors.

Do I need to be screened if I’ve had the BCG vaccine?

Yes. The BCG vaccine can cause false positives on the tuberculin skin test (TST), making it hard to interpret. For people who’ve had BCG, the interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) is preferred because it’s not affected by the vaccine. IGRA is more accurate in this group and should be used if available.

How long after starting a TNF inhibitor does TB usually appear?

Most cases occur within the first 3 to 6 months of starting treatment, especially with infliximab and adalimumab. But TB can develop anytime-even years later. That’s why ongoing symptom checks every three months during the first year are critical, even if you were screened and treated for latent TB.

Can I start TNF inhibitor therapy while still on TB treatment?

No. You should wait until you’ve completed at least one month of latent TB treatment before starting a TNF inhibitor. Starting both at the same time increases the risk of TB-IRIS, a dangerous immune reaction. For active TB, you must complete full treatment (usually 6 months) before considering TNF inhibitors at all.

Is TB screening required for all TNF inhibitor patients?

Yes. Major guidelines from the CDC, ATS, and EULAR all recommend universal screening before starting any TNF inhibitor. This applies regardless of where you live now-your past exposure matters. Even if you’ve lived in a low-TB country for years, if you were born in or spent significant time in a high-burden country, you need screening.

What if I can’t afford or access IGRA testing?

If IGRA isn’t available, use the tuberculin skin test (TST). In high-risk patients, consider a two-step TST to reduce false negatives. Some clinics use booster TSTs to improve accuracy. While IGRA is preferred, a well-performed TST is still valid. The most important thing is not to skip screening altogether.

Mark Curry

December 5, 2025 AT 22:23Been on Humira for 5 years. Never had TB, but I always get the IGRA now. BCG shot in India as a kid, so TST was useless. Glad they're pushing better screening.

Still freaks me out thinking about how one shot could wake up something buried for decades.

Thanks for laying this out clearly.

Manish Shankar

December 7, 2025 AT 10:30As a physician from Mumbai, I can attest that the risk is not theoretical here. We see TB reactivation in nearly one in seven patients on monoclonal TNF inhibitors. Many patients come to us with disseminated disease because they were never screened. The cost of IGRA is prohibitive for most. We use two-step TST as a stopgap, but it is far from ideal. Global equity in rheumatology care remains a silent crisis.

Lynette Myles

December 8, 2025 AT 17:01They’re lying about etanercept being safe. The FDA data shows it still reactivates TB-just slower. They’re pushing it because it’s cheaper to sue people later. You think they care if you get spinal TB? No. They care about stock prices.

Annie Grajewski

December 9, 2025 AT 10:35so like… if i had tb in 1998 and now i’m on humira… i’m basically a walking time bomb??

also why do we even have these drugs if they just turn us into tb magnets??

someone please tell me the point of modern medicine if it’s just ‘here’s a miracle drug that might kill you in 6 months’

lmfao

Norene Fulwiler

December 9, 2025 AT 18:44As a Black woman from a family that came from Nigeria, I’ve had my BCG shot, my TST, my IGRA. I’ve been told I’m ‘high risk’ since I was 18. But no one ever told me that my doctor might skip the IGRA because ‘we don’t have it.’ I had to push. I had to demand. This isn’t just medical-it’s racial. If you’re from a ‘high-burden’ country, your life is treated like a statistical afterthought.

Katie Allan

December 9, 2025 AT 21:37This is one of the most important posts I’ve read all year. Thank you for the clarity. As a nurse in London, I’ve seen patients dismissed because ‘they’ve lived here 20 years.’ But TB doesn’t care where you live now-it cares where you lived then. We need mandatory screening protocols, not suggestions. And we need to stop acting like IGRA is a luxury.

Deborah Jacobs

December 10, 2025 AT 00:47I got on Enbrel because my rheumatologist said, ‘You’re from the Philippines-you’re not getting the antibody stuff.’ I didn’t even know what that meant until I Googled it. Now I’m the person who tells every new patient, ‘Ask about the TB thing. Don’t just sign the paper.’

It’s not scary because of the drug-it’s scary because no one talks about it until it’s too late.

Michael Dioso

December 10, 2025 AT 19:12Oh wow, so the ‘safe’ drug is the one that doesn’t work as well? And we’re supposed to just accept lower efficacy because TB is ‘too risky’? That’s not medicine-that’s surrender. If you can’t handle the side effects, don’t take the drug. Simple. Stop coddling people with screening protocols like they’re toddlers.

Krishan Patel

December 11, 2025 AT 17:25How can anyone in the West complain about TB risk when we have over 2 million cases annually in India alone? You think your IGRA test makes you safe? You are merely delaying the inevitable. The real issue is not the drug-it is the global collapse of public health infrastructure. Stop blaming pharmaceuticals and fix your own systems.

sean whitfield

December 12, 2025 AT 01:40Screening? Monitoring? Please. They just want you to come back every 3 months so they can bill you. The real reason they push IGRA is because it costs $200 and insurance pays for it. The drug companies know this. They made sure the guidelines are profitable.

Etanercept? More like ‘Ethan’s little profit maker.’

Carole Nkosi

December 13, 2025 AT 12:44My cousin in Johannesburg died from TB after starting adalimumab. They told her she was ‘low risk’ because she was ‘clean.’ Clean? She was born in a township with open sewage. No one tested her. No one cared. This isn’t science-it’s colonial medicine dressed up in white coats.

Philip Kristy Wijaya

December 14, 2025 AT 12:12It’s funny how everyone acts like TNF inhibitors are new. They’ve been around since 2000. The TB risk was known in Phase 1 trials. The FDA approved them anyway. The only difference now is that we have better data to prove what they ignored. You don’t need a doctor to tell you this. You need a lawyer.

an mo

December 14, 2025 AT 21:10Let’s be real: the entire TNF inhibitor class is a regulatory failure. The mechanism of granuloma disruption was modeled in 1999. The FDA ignored it. The EMA ignored it. Pharma knew. They marketed it as ‘miracle drugs’ while the latent TB burden in immigrant populations exploded. This isn’t negligence-it’s calculated risk transfer to the poor.